COP 22- Madagascar: « We can avoid famine if we take preventive measure »

Opinion article

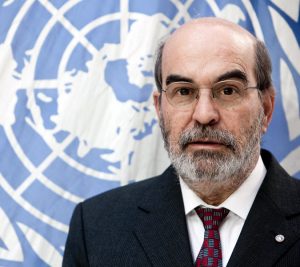

By José Graziano da Silva*

In the past months a number of regions have been hit hard by the El Niño phenomenon, the effects of which are still posing a global threat to agricultural livelihoods. The most affected include the Horn of Africa, Southern Africa, Central America’s Dry Corridor, Caribbean islands, Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands.

Scientists are now predicting the probable occurrence of the « opposite twin » phenomenon, La Niña. This could increase the chance of above-average rainfall and flooding in areas that have been affected by El Niño-associated drought.

For Madagascar, La Niña could have serious consequences, such as increasing the intensity of cyclones and tropical storms thus aggravating the food insecurity of the country’s rural population, whose capacity to face climate shocks is already fragile.

Madagascar has the potential to become the granary of the Small Island Development States of the Indian Ocean. However, it is also one of the 20 countries in the world that are most vulnerable to climate change – in Africa it is the fourth most vulnerable country in terms of recurrent cyclones and tropical storms.

The 2015-2016 agricultural season has seen a dramatic reduction in crop production in southern Madagascar mainly due to a severe drought. In particular, production of maize and cassava crops this year declined by up to 95 percent compared to the previous five-year average — last year it was over 80 percent. Vulnerable households, whose already-low purchasing power is eroded by prevailing high prices, have been forced to adopt multiple survival strategies, especially in Madagascar’s seven southern regions.

Currently available estimates indicate that the number of food insecure people in southern Madagascar exceeds 1.4 million in September 2016. Of these, 600,000 are considered as severely food insecure, which according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) scale represents the last stages before the famine phase. They need immediate emergency assistance: hungry people can’t wait.

In the recent past, most of the attention of the international community has been given to the dramatic impact on food security caused by several conflicts. FAO has been highlighting the cases of countries such as South Sudan, Yemen, Syria and regions such as Lake Chad, where millions of people are in a severe food insecurity situation. Yet, this should not stop to pay attention to other crises that are not capturing the media attention.

The international community is urged to step up to prevent a repeat in Madagascar of the situation faced by Somalia in 2011, when 200,000 people died of hunger for lack of speedy response.

Somalia taught us a crucial lesson: if we provide people with cash, they will find food. This is the Zero Hunger approach: access to money to revitalize local production and local markets. Then distribute seeds so that they can replant. In sum, to promote local development.

Emergency interventions provide a short-term solution and must be implemented immediately to assist vulnerable households. These actions need to be complemented by medium term, interventions aimed at building the resilience of rural communities so they can deal better with future shocks, overcome chronic poverty and safeguard their livelihoods..

The Zero Hunger approach includes cash transfers as part of emergency social protection measures that allow people to access food. In addition, small-scale farmers need be assisted in preparing for the upcoming planting season through the provision of seeds, fertilizers, tools, irrigation equipment and other inputs while also helping them store water for human and animal consumption – capitalzing on spite the rainy season that we hope will start soon in Madagascar.

We all have recognised during the World Humanitarian Summit of Istanbul that ending poverty, hunger and malnutrition must become the basis of a new social contract in which no one is left behind. We have a second chance now. This is what the Sustainable Development Goals are all about and it is key to resolving the world humanitarian crisis.

We must act immediately since the effects of La Nina could be felt as early as October – there is now a 55 to 75% probability of La Nina. Thousands of vulnerable people in the south of Madagascar can’t wait; they will try to survive by starting to migrate to other regions and a failure to intervene will mean the situation will get worse.

Two things are urgently needed in this moment: the political will to take decisions and the support and resource mobilization from the international community. The partners I met during my visit to Madagascar early September agree that this is the right way to act. Our strong message is: we must pay attention to what is going on in Madagascar. This is a fragile democracy that needs global community assistance. We need to act fast.

* José Graziano da Silva is Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).